The year I turned eleven years old, my parents stuffed us kids in the car and drove to Mississippi from Washington, DC to visit kinfolks in the house where my dad had grown up, and to do the things we did there every summer with the cousins and aunts and uncles and hangers-on. We’d find ourselves with a few minutes of fame because our names would appear in Myrtis Rogers’ column of Happenings, written up in the local paper as returning once again to visit, in a town where there was absolutely nothing to do but melt into the non-airconditioned heat and humidity, wander the cemetery, plunk the piano in the unlocked Methodist church, and read Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland one more time.

We had our routines. My great-grandmother, Nanny, would work in her garden in the early morning while her daughter, my grandmother, made dinner in the middle of the day. After dinner, my grandmother pulled the tablecloth up by the corners and draped it over the food on the table, to save it for suppertime. Nanny watched “As the World Turns” and then took to her bed to read the newspaper until she fell asleep in the hottest part of the day with the paper in a tent across her face The attic fan droned like an idling airplane engine, as it pushed the hot air around the house.

I’d help Annie Mae shell butterbeans on the front porch. I’d go to the post office with my grandmother, then to Mr. Jeff’s store to stock up on 6-ounce Coca Colas in glass bottles that would line the inside of the refrigerator door when we’d arrive (what treasure!). I’d listen to the old folks swapping the same old stories on that same old porch in the evenings, moths dancing around the porch light as the day cooled enough for the adults to brave sitting outside with a slice of coconut cake and conversation to go with their sweet tea.

My brother and I slept in the spacious “back room,” a room that my father — a pilot and not a carpenter — had built onto the house as a young man, many years before. The room spanned the back of the house and held two big beds with iron frames and feather pillows and springy mattresses. The beds sat perpendicular to each other on opposite sides of the room. There was a mysterious built-in closet. It’s door was positioned flush with the exterior wall, so its innards protruded to the outside, giving the exterior wall a decided bump-out. My brother and I tried opening that door once, and found it locked.

A built-in bookcase housed milk glass, a vase with dead (or were they dried) flowers, and a clutch of dusty books. A chest of drawers was decorated with a crocheted doily and a fold-out trio of 8x10 framed photos of my dad and his two sisters. The floor of this long wide room sloped just enough that you could place a marble at one of the two doorways (one opening directly into my parents’ bedroom and one opening to the only bathroom in the house) and watch it roll in a lazy, bumpy pattern across the planked floor to the outer wall of the room, where it would settle with a clack under the treadle sewing machine.

The room was a time machine. I adored it.

The year was 1964. These were sleepy days in a sleepy Mississippi town with one unnecessary stoplight and a train to Laurel that no longer stopped there. Time had already forgotten Jasper County, Mississippi, or had it? 1964 was the year that “everything closed” and no one in my small world talked about it to us kids. But, of course, we noticed. And we had questions.

In the county seat of Bay Springs, which was seven miles from my grandmother’s house in Louin, Mississippi, the Lyric Theater closed. We rarely went to the movies, but the summer I was eight — or was it nine — I had watched an Elvis movie with a local friend who was older than I was by three years and was mad about Elvis. It would be some years before I appreciated Elvis Presley, but I wanted a friend in this town where there was nothing to do, so I sat through that rather-confusing movie and was content with popcorn in the dark, a summertime friend, and luxurious air conditioning.

The summer I turned eleven, the Lyric closed. So did the Cool Dip, where we’d get ice cream now and then, and so did the public library. Between Louin and Bay Springs was a little pass-through on a curving two-lane road traveled by logging trucks that we called Pine View. There was a cafe on one side of the road — the Pine View Cafe of course — where they served blue plate specials cooked fresh every day, a meat-and-three destination for locals. It closed.

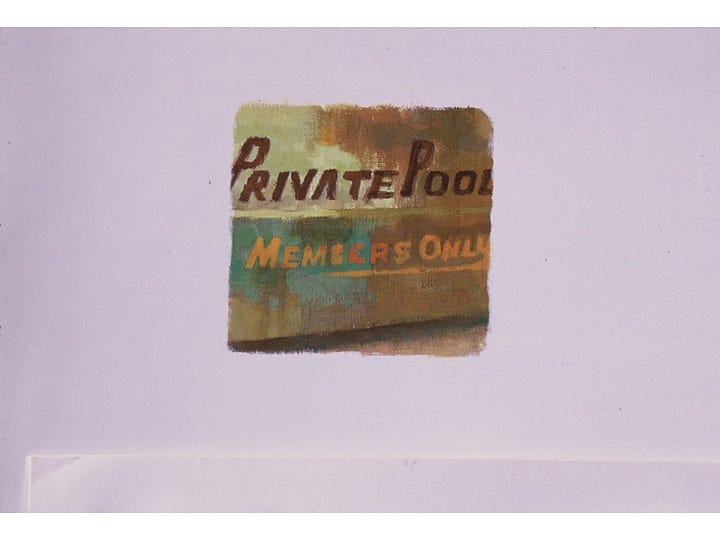

Across the road from the cafe sat the Gem of Summer for me: the Pine View pool and the roller skating rink. I could convince my parents to take us there at least once a summer. I lived for that outing.

The pool and the roller skating rink were nestled against a pine forest on two sides and the railroad pond on another. The train that picked up passengers in Louin long ago stopped at the railroad pond to take on water, hence the pond’s name. I have a photo of my parents, before the world had touched them, sitting on the steps of that porch at my grandmother’s house with their fishing poles between them, holding a clutch of catfish on a stringer. My heart catches, every time I see it. They are so young. So young.

Eventually — not that summer, but one summer in the future — the library reopened, but all the seats had been removed. The Cool Dip closed its indoor seating, so you had to order your frozen treats at a hastily constructed window that abutted the too-small parking lot. The Lyric never recovered, and the Pine View cafe and pool and roller skating rink fell into abandoned disrepair.

The summer was called “Freedom Summer,” or if you were part of the Movement that year, “The Mississippi Summer Project.” The Project had been hastily decided upon (yet, miraculously, meticulously planned) to coincide with the signing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Across the South especially — but not only the South — the response to the passage by Congress and signing by President Lyndon Johnson of this new Federal legislation into law was swift and intentional.

Many towns in Mississippi, such as Greenwood, in the Delta, had much more visceral responses than a sleepy rural town like Louin, but the reverberations were felt across the country, and they are still being felt today. .

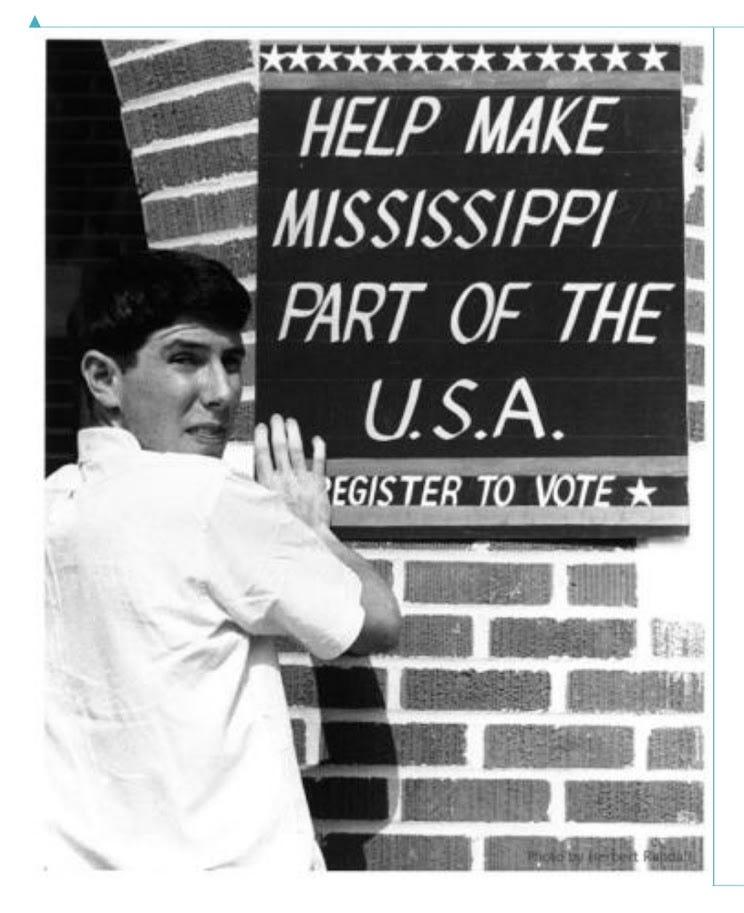

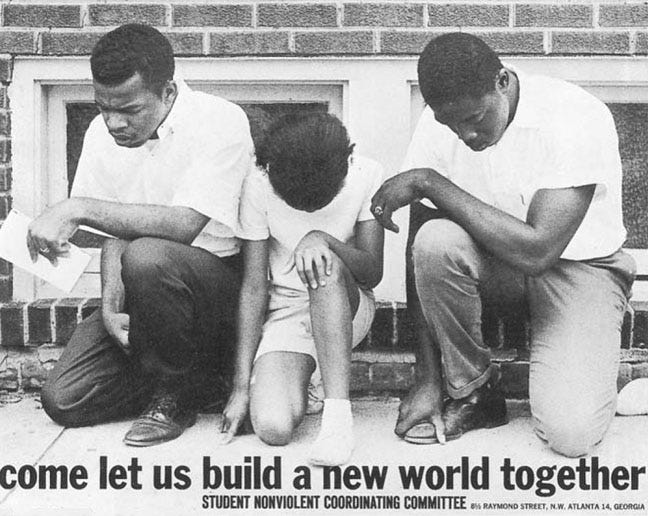

One thousand souls came South to Mississippi in 1964, most of them white, many of them college students who had been recruited by CORE or SNCC or COFO on their college campuses. They trained in techniques of passive non-violent resistance at Miami University in Ohio, they boarded busses for their Mississippi assignments, and they lived in Black communities, with Black families and volunteers.

Their project was to register Black voters in the state of Mississippi, “the Closed Society,” where Blacks had been disenfranchised since 1890 at the death of Reconstruction. The Freedom Summer volunteers were to open Freedom Schools where Black children and families could learn their history and basic educational skills, and to rent houses in the Black community to serve as community centers and Freedom Houses, where everyone could congregate to be together and learn and plan the next days’ actions. Volunteers would also go to the courthouses with prospective new voters so they could register to vote in the next election. When Black citizens (and white and black volunteers) were arrested, beaten, and harassed to the point of not being able to register at all, volunteers simultaneously worked to register their new voters themselves in order to form a new Freedom Democratic Party to be seated at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

The volunteers were in Mississippi to support Black activists who were already on the ground working in their communities; to bolster their efforts; and to leave them at the end of the summer with as many tools of support — and new voters — as possible.

It would be decades before I researched what had happened, that childhood summer of mine, before I met my heroes in print: Ella Baker, Bob Moses, Bayard Rustin, Fannie Lou Hamer, Casey Hayden and countless volunteers both local and national, including the Wednesdays Women who worked tirelessly from “up North” to bridge gaps of understanding between black and white women, who flew South weekly to meet over tea and talk and to foster understanding between courageous black and white women in Mississippi towns, and who helped to raise funds up North to send to Freedom Houses for the work they were doing, in hopes of making change and forging a path for future generations.

There was an energy in the air, the summer of 1964. Eleven-year-old me could feel it, too, could feel some kind of enormous, serious, almost-dangerous change in the hot, humid, over-emotional atmosphere in Mississippi, even if I couldn’t name it.

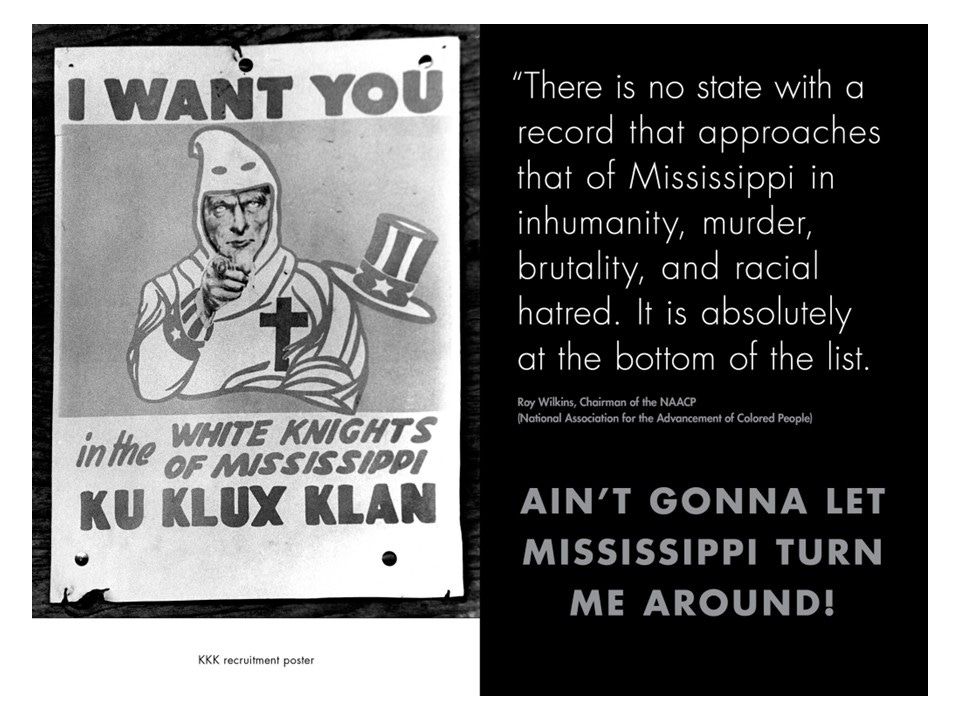

Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner went missing on June 21, 1964. It was Andy’s first day as a Freedom Summer worker; Mickey and James had been working with COFO in Meridian for some time. They picked up Andy and drove to Neshoba County, Mississippi to investigate a church burning. When their car got a flat tire outside of Philadelphia, Mississippi, Deputy Sheriff Cecil Ray Price arrested Cheney for speeding and held Goodman and Schwerner for investigation. All three were taken to the Neshoba County jail.

Later that night, they were murdered by local members of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. Their bodies were not found until August 4, as the Mississippi Summer Project was wrapping up and the Mississippi Freedom Party delegation was heading North to the Democratic National Convention with 80,000 new voters on its rolls, voters black and white, Mississippians who were not required to take literacy tests in order to vote, and who could register in their homes, with a Freedom Worker to sit with them and help them fill out the paperwork, if necessary.

There had been uncountable numbers of arrests, beatings, lynchings, harassments, threats, bombings, torchings, and tortures of Black Americans throughout Mississippi through the decades, and the summer of 1964 was no exception.

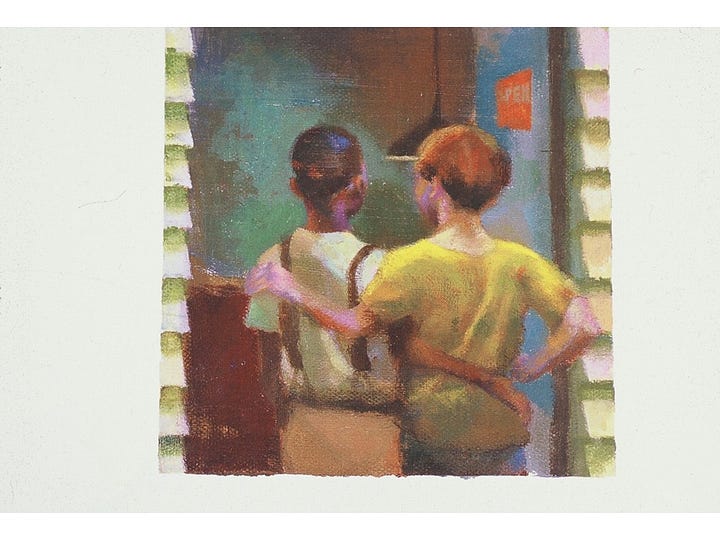

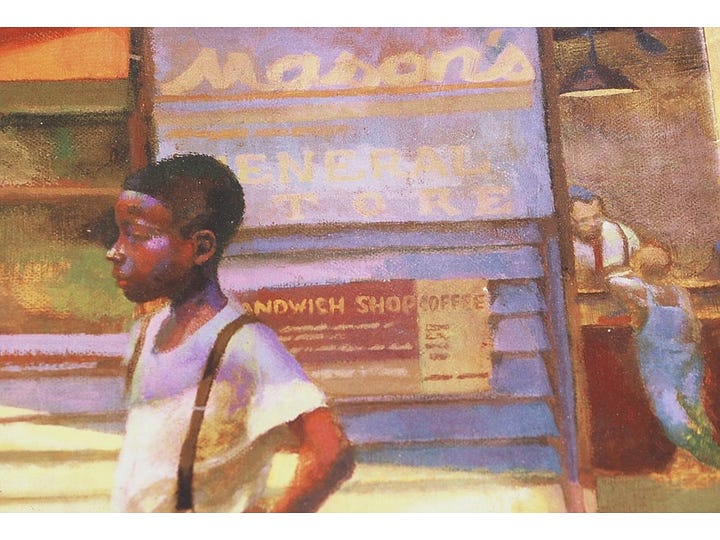

When I’m working with young people, and especially when presenting my books, Freedom Summer — which is a picturebook about the closing of the pool — and Revolution, which is a documentary novel for middle schoolers and older, about the summer of 1964 in Greenwood, Mississippi, which was the headquarters of SNCC, I always tell them that every human being is worthy of dignity and respect, and that it’s hard to hate someone when you know their story.

Even as I say it, I think of that summer in Mississippi and of the crimes committed in the name of white supremacy and white power and control, and out of the white fear of being replaced. We see that power-grab and white fear across the country in present day, too, in the very public deaths of those whose names are so familiar to us now: Sandra Bland, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, George Floyd and so many more — people who had mothers and grandmothers and sisters and brothers and summertime rituals. They had routines and tablecloths and Sunday dinners and movies and ice cream and kinfolks and porches or stoops and bodies of water to swim in or rooms with sloping floors.

I think about Lillian Smith. Smith was a white writer, educator, and human rights advocate who lived in Rabun County, Georgia, in the North Georgia mountains. She fought all her adult life against segregation and racism at a time when few white voices did so, so vocally. In 1920, her parents started a private summer camp for young white girls from Atlanta families of means, and (among other amazing accomplishments) Smith made it part of her work to educate these young ladies about the South they lived in, to help them envision change and question everything they had been taught about the status quo and segregation in the American South.

In 1949 she wrote the ahead-of-its-time book Killers of the Dream which begins:

Even its children knew that the South was in trouble. No one had to tell them; no words said aloud. To them it was a vague thing, weaving in and out of their play…. they had seen it flash out and shatter a town’s peace, had felt it tear up all they believed in. They had measured its giant strength, and felt weak when they remembered.

In a 1961 letter to her editor, upon a new edition of the book being published, she wrote:

I am caught again in those revolving doors of childhood… it is a book brought to life, I see plainly now, by young questions that begged for sane answers…

And then she writes a sentence that speaks to me across the years about what I write and why:

I wrote it because I had to find out what life in a segregated culture had done to me, one person. I had to put down on paper those experiences so that I could see their meaning for me.

Lillian Smith firmly believed that racism hurt all people, all colors, all nationalities, all identities, all. We hurt ourselves when we hurt other people. Every human being has a beginning. How do we take care of one another in such a way that we render ourselves harmless and we are, all of us, unafraid?

When Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968, Robert Kennedy Sr. was campaigning for president. He landed in Indianapolis minutes after he heard the news. He put aside his campaign speech and spoke to a waiting crowd that — in an age before cell phones and a 24-hr news cycle — did not know yet about King’s death.

RFK broke the news to them in a simple, heartfelt speech that I go back to again and again. The entire speech is worth reading, and the line that comes to me as I finish this essay is, “Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world.”

And that is why I write. I, too, am caught in those revolving doors of childhood, hoping to connect with readers who, no matter their ages, are still like all of us, young people begging for sane answers, and I am still that child of a Mississippi summer reaching for meaning, self-understanding, and change.

Debbie, I clung to every word of this. The similarities between then and now, when we should know and be so much better, are beyond disheartening. I take comfort in those last two paragraphs–in Kennedy's words as a reminder that savageness can and should be overcome and in the hint of mission I see in that last paragraph and the hope that exists there.