Storybelly Extra: The Messy Glory of Grief and the Birth of Each Little Bird That Sings

The Ways We Write About Home

An extra free post this week to celebrate the birthday of Each Little Bird That Sings. In the Writer’s Lab tomorrow, we’re working with how we write about home, in all its messy glory. You can sub to the Lab at the bottom of this page, if you haven’t already, to work/write/chat along with us, in a safe, companionable and communal writing space. Onward:

I wanted to sell Hang The Moon, a novel I started writing in 1995; its four chapters had won the PEN Naylor award in 2004. That novel is a story for another day… it still shows as “untitled” and “available for publication” at the Pen/Naylor page on the PEN America website… maybe one day it will exist as a novel in the hands of a reader…. but I digress.

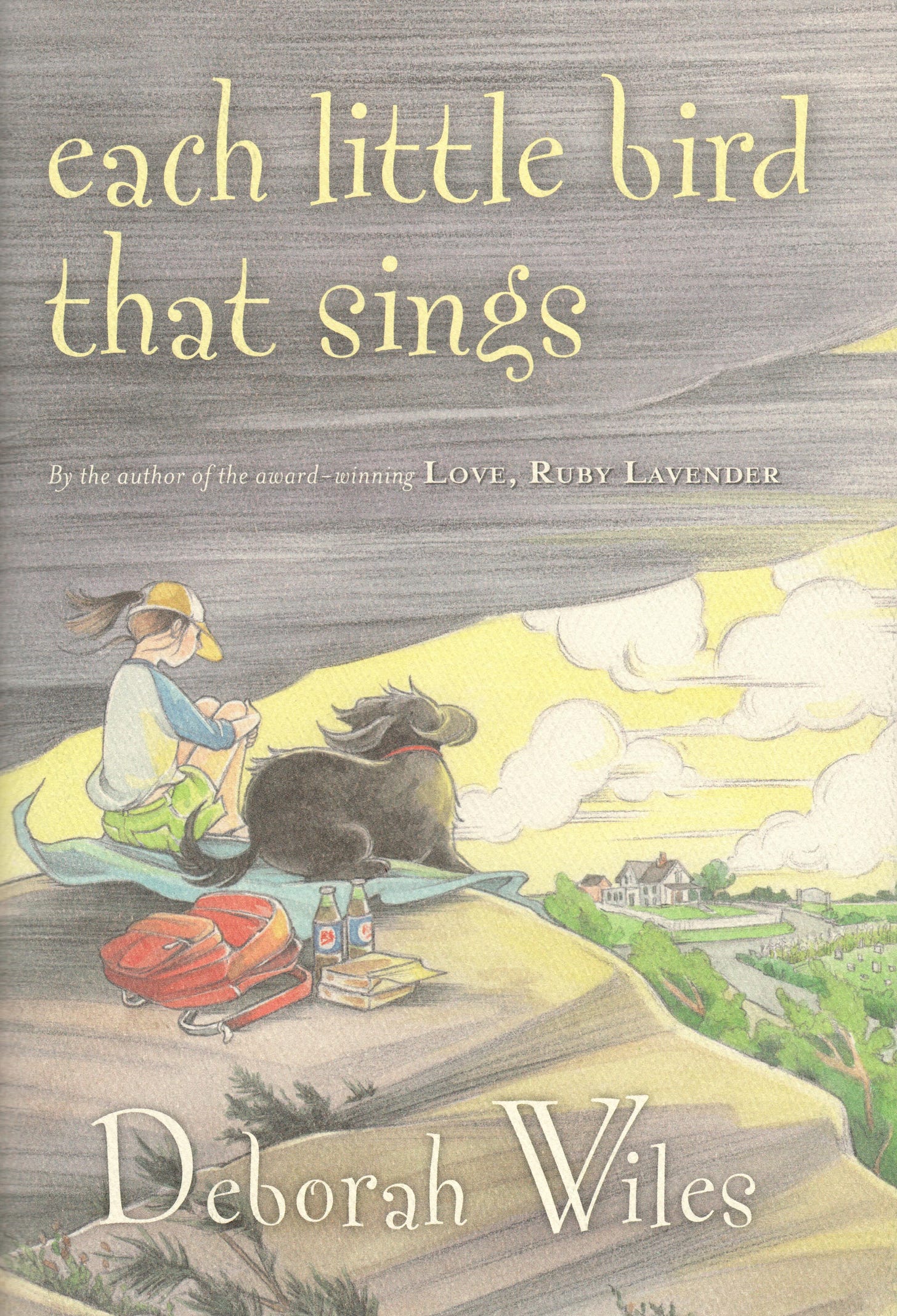

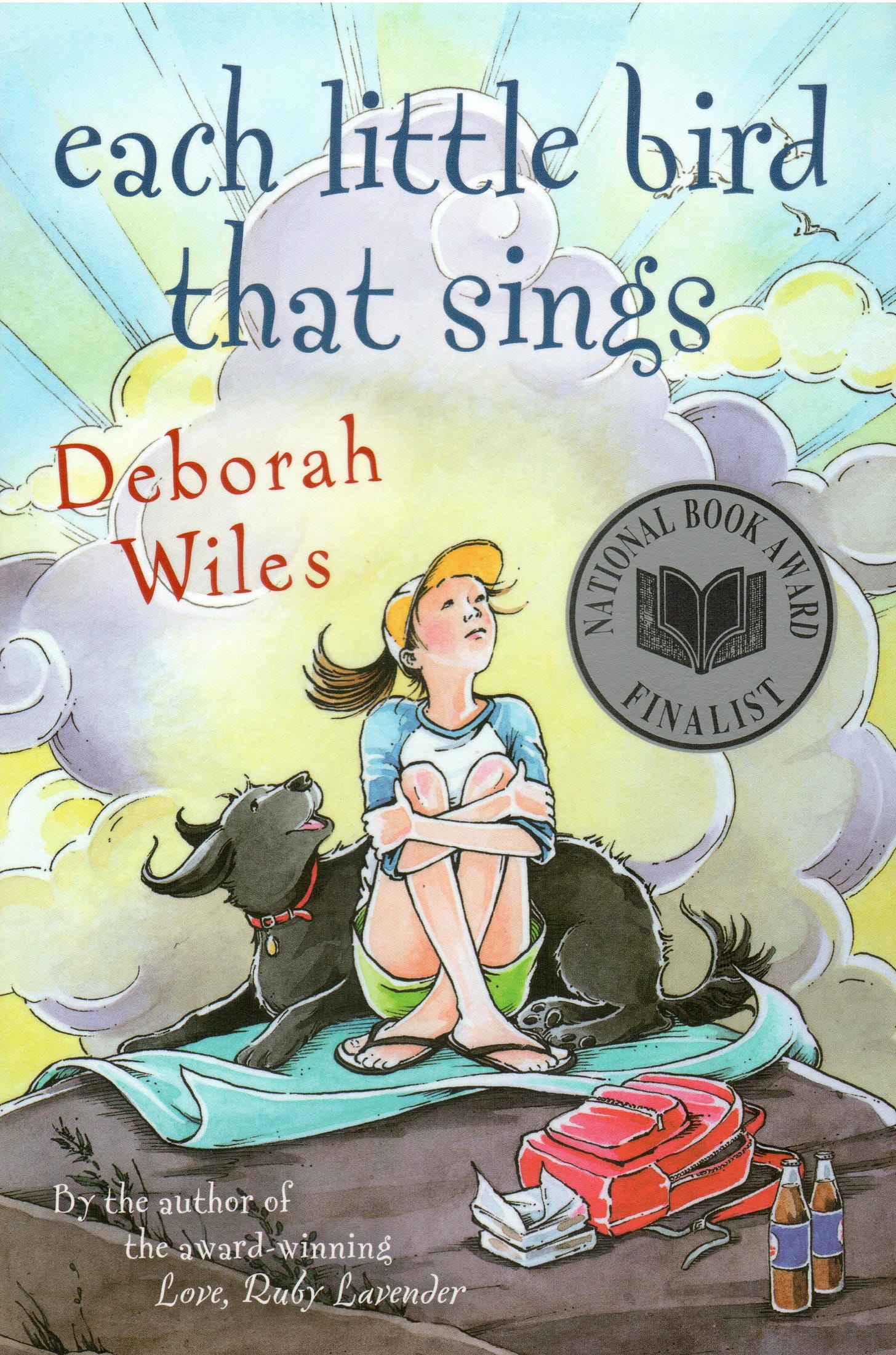

What I wrote (eventually) and sold instead was a novel about grief and loss and finding home again, in the guise of a ten-year-old girl who suffers loss after loss and who finds her way through with the help of understanding adults, family traditions, an over-organized brother, an over-bouncy sister, patient parents, and an overly-neurotic cousin she would like to throttle.

I wrote this story, which became Each Little Bird That Sings, inside a rush of my own losses, unfathomable to me at the time, overwhelming beyond belief, and in the midst of starting over with just about everything in my life. There was no social media in the year 2000, and what I have of those days is an extensive email trail, although much of it in those early days is lost. I also have obituaries: both my parents, my long-years marriage, my home, my full-time mothering, the good-old-girl family dog, financial solvency, my life as I knew it.

These losses began in an epic cascade two weeks before Freedom Summer, my first book, was launched, and three months before my first novel, Love, Ruby Lavender, was published. I wouldn’t write another word for publication for the next three years, didn’t think I would ever write again, until my editor, Liz Van Doren at Harcourt Brace, asked me to make her a promise.

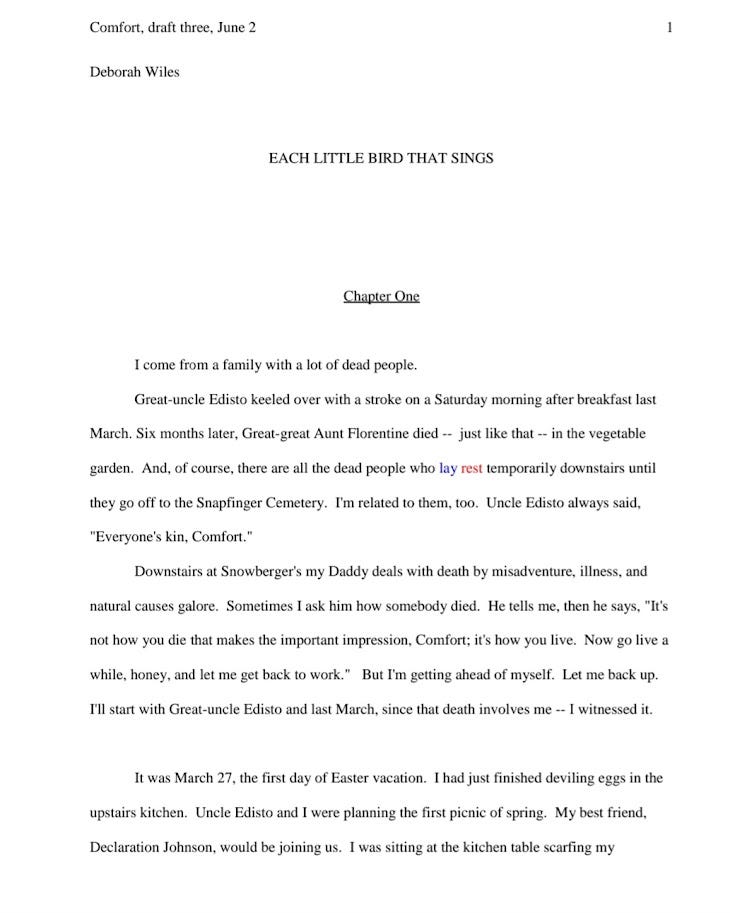

“I want you to sit down every day and ask yourself, ‘what can I write?’ and send it to me.” And that’s how Little Bird was born. I wrote about my grief, and sometimes all I could write was “SAD.” I sat in the back room of Cindy Powell’s quilt shop, Needles & Pins, on Church Street in Frederick, Maryland, and cried. Cindy’s mother, never one for self-indulgence, visited the shop one day, saw me sitting there, weeping, surrounded by bolts of fabric and batting and notions and said, in so many words, “You will not always feel this way. You are not the only person these things have happened to. You are not unique!” And then, basically, “Take up thy bed and walk,” although it would take time for me to learn how to do that.

People brought food to the house. I lost 60 pounds. My teenage son (who is now my ops-guru) left me notes: “Mom, I made you some food. It’s in the refrigerator. Please eat.” I stood in the Hallmark aisle without enough money to buy a thank you card at a bookstore and burst into tears at the roses, hearts, and sentiments on those stiff-backed, happy cards for lucky people, cards that declared undying love and thanks to a spouse, to a daughter, to a life that was whole, when mine had fallen apart.

“We are still a family,” I told my kids. I hoped I was right. The fuel oil company sent me coupons to send in with my monthly payment, so I could afford heat. A neighbor cleared the tree that fell across my driveway in a storm. Others took my growing pile of green trash bags to the dump when I couldn’t afford trash service. Friends financed me until I could finance myself, they found me work, I began to teach. I buried my parents and began my life as a road warrior, where I would remain for the next 22 years, as I wrote books in the cracks and dreamed about coming home to write full time. My friend Kay gave me her boots and a sturdy winter coat, dressed me for the road, fed me at her kitchen table, had her husband, Doug, teach me how to keep ledger sheets (by hand!) to create a budget, and my friend Sue sheltered me in her home when I worked in DC schools after I’d had to sell the home I’d lived in for fully half my life and relocate.

I was still writing in my notebook, “SAD,” and sometimes elaborating on that sadness, but I had no direction. One night, at a rare dinner out with Cindy and Kay (“Come on, it will do you good.”) Kay told the story of growing up a child in the fourth family of her grandfather’s, after his many failed marriages and being surrounded by so many much older brothers and sisters, aunts and uncles and various kinfolks who were “dying by the handful every year.”

“Believe me,” she said, as Cindy passed the homemade garlic rolls and we settled in for Kay’s story, “I went to a LOT of funerals, growing up. We’d walk into the funeral home so often that people working there began to say, ‘Here come the Snowbergers again!’”

It felt good to laugh — you had to have heard Kay’s natural-born storyteller delivery and her tales of funerals past, and how Cindy chimed in with “Always be the pace car at a funeral, when you go to the cemetery. That way you can escape before all the fighting starts.” I laughed so hard I cried, a great release, and then Kay offered that quintessential line:

“Let me tell you, Debbie: I come from a family with a LOT of dead people!” We dissolved into the kind of helpless laughter that brings the wait staff over to make sure you’re okay.

“I need to write that down,” I said. And Kay, ever prepared for all contingencies, whipped a yellow Post-it note pad from her purse, and a pen, and handed them to me across the table.

I still have that note. “Can I use your maiden name?” I asked her. She waved a hand above her like she was conferring the name upon me. “If you ever write about all this mess you’re living through, I hope you do.”

And of course I did write about this mess. I used that line from Kay as the first line of what would become Each Little Bird That Sings. I named my main character Comfort, because I needed so much comfort as I wrote my heart out, and I needed perspective, so I created two older characters who I dispatched in the first chapters, but who wove some much-needed humor through a story that I thought would be all about death, but it turns out was all about life. “Open your arms to life!” Uncle Edisto tells Comfort. “Let it strut into your heart in all its messy glory!”

I sent a sudden chunk of chapters to my editor with a note: This is what I can write. She sent me back an email of two words: Keep going.

I wrote Each Little Bird That Sings in less than a year. I set it in a funeral home, of course, and Comfort’s family owns this funeral home — Snowberger’s Funeral Home. Her family is whole, intact, loving, devoted, and stable. When trouble comes, and it does, they weather that trouble together, albeit crazily, but with great heart and humor and stumbling grace. So comes wisdom… and healing.

Comfort’s orderly world gives her the space to write “Top Ten Tips for First-Rate Funeral Behavior,” and “Fantastic and Fun Funeral Food for Family and Friends.” She writes “Life Notices” for the departed, which is what I started doing, and what legions of young writers did with me, for many years.

Comfort has her life figured out until her neurotic cousin Peach shows up to topsy-turvy everything. Comfort learns to let go of what she cannot control, to accept the things she cannot change, and to change the things she can. Her best friend betrays her. Great-great Aunt Florentine dies in the vegetable garden — poof! her skirt flowing around her — while weeding the peas. Peach prostrates himself on her casket at the funeral. Uncle Edisto opens his arms one last time to life and then expires after a picnic. Comfort’s dog, Dismay, goes missing. It’s a sh*tshow of loss and grief, and I was there for it. I couldn’t stop writing about it.

Liz caught each chapter as it landed in her email inbox. She read it, responded, I revised, and wrote more. I had no idea where it was coming from, but of course it was coming from my life. It was teaching me how to live again.

And I *was* living again, slowly, surely, moving into a new life, in a new town and a new home, with new adventures, new books, new everything, eventually becoming the age of my parents, watching my children grow up and find love of their own, bury their father, birth their children, life going on, while we, it turns out, are still a family.

We are differently configured, as happens to all families, and yet we are whole, intact, loving, devoted, and stable. When trouble comes, and it does, we weather that trouble together, albeit crazily, but with great heart and humor and stumbling grace.

The messy glory. I am one of many, as Cindy’s mother told me that day at the quilt shop. I am not unique. But Comfort is. There is only one of her in the world. Only one Each Little Bird That Sings. And this is the story of how she was born, and how she saved me.

Thanks for sharing today Debbie. I'm very familiar with the darkness that comes with loss and depression. I think it's part of being human. I'm also grateful to have been able to climb out of that darkness. It makes me happy for you to see that you've been able to find the strength and the help from your friends and family to not give up. We are not alone although it sometimes feels that way.

You tell the best stories about your books!